County clerks across Colorado say they’re bracing for a surge of highly motivated election deniers working as poll watchers or election judges in the November midterms — part of a nationwide attempt to manufacture evidence of election fraud.

Local, state and federal officials, alongside political experts, have repeatedly debunked claims of election fraud but clerks in Chaffee, Eagle, El Paso, Fremont, Garfield, Summit and Weld counties told the Denver Post they’re still seeing an increasing number of bad-faith poll watchers and election judges around the state.

Encouraged, even recommended, by party officials or far-right voices with national reach, the clerks say those watchers and judges have antagonized or threatened election workers, wrongly rejected hundreds of ballots and one man in Chaffee County even tried to steal a password to the election system last year.

The irony sits in the notion that these far-right election judges and poll watchers are damaging the country’s foundation of fair and free elections, all under the guise of fighting for election security, Larry Jacobs, a professor of political history, elections and voting behavior at the University of Minnesota, said. Their goals appear to be to sow doubt and prop up losing candidates. The effort continues former President Donald Trump’s work to overturn the 2020 election except it’s now more sophisticated.

“It’s moved from spur of the moment, ad hoc, to an organized, well-funded, premeditated effort to make charges of election fraud,” Jacobs said.

Election officials should prepare for widespread claims of fraud following the upcoming November midterms, Jacobs said. The severity of those claims in the months to come could serve as a bellwether for the already contentious 2024 presidential election.

Federal officials have repeatedly said that the country’s elections are not at risk from outside interference but at the same time, CBS reported that election officials in seven states — Colorado included — are dealing with more and more threats to their personal safety.

County clerks put forward an air of optimism, but the changing landscape of American elections is wearing on them.

“Every day you wonder ‘What fresh hell is today going to bring?’” Chaffee County Clerk Lori Mitchell said. “These things are coming out of nowhere and you’re just trying to do the best you can.”

Mitchell and her colleagues are ramping up training efforts to help staff de-escalate potential conflicts and tighten security measures. But most of all they’re leaning on the most powerful tool they have: transparency.

The clerks are inviting all those who doubt that Colorado is home to the country’s gold standard of free and fair elections to see the process in action. These clerks live in a world of spreadsheets, bipartisan teams, chains of custody, signature verifications, logic and accuracy tests and risk-limiting audits. They each exude a passion for the process and a sense of pride in converting doubters into believers.

Even so, there are those who remain unconvinced.

“We built a campaign going into 2022, daring them to do the same thing they did in 2020, certain people, certain actors in certain areas,” conservative radio host Joe Oltmann told The Denver Post. “We know that the system is compromised. The judiciary, the legislative branch is compromised.”

Vicky Tonkins, chair of the El Paso County Republican Party, said she believes ballots were cast on behalf of dead people in the 2020 election, questions the accuracy of her county’s voter rolls and expresses confusion that even though Trump received a higher number of votes in 2020, his overall margin of victory in El Paso County shrank.

“This is the first time in many years when people have been this engaged,” Tonkins said. “If you can’t be questioned and prove that you are the gold standard then what are you trying to hide?”

“What are they willing to do to get their 15 minutes of fame?”

County clerks across Colorado say they’ve seen election deniers in every election since 2020. They’ll volunteer as poll watchers and some even work as election judges.

Watchers do just that. They watch as clerks, their staff and judges prepare ballots, verify signatures and count votes, El Paso County Clerk Chuck Broerman said. They can represent a political party, a specific candidate or those backing a certain ballot issue.

Election judges actually participate in the process, working certain machines, collecting drop boxes, verifying signatures and more, Broerman said. Judges are appointed by political parties and work in bipartisan teams to ensure fairness.

Some watchers and judges come in with a confirmation bias, expecting to find fraud, Broerman said. Others are trained by election denial groups to look for certain things and ask specific questions designed specifically to bolster a fraud claim.

Coming into the process convinced fraud is already happening puts the entire system at risk, Matt Crane, executive director of the Colorado County Clerks Association and former Arapahoe County clerk and recorder, said.

“If somebody comes in thinking they’re going to find a kraken and they’re hell-bent on finding a kraken, what are they willing to do to get their 15 minutes of fame?” Crane said.

Telling the bad actors from the legitimate volunteers is a difficult task, Broerman said. At times impossible.

In late September Tonkins – for unclear reasons – removed three of the county Republican party’s longest-standing election judges and replaced them with new, unfamiliar ones, Broerman said.

“It seems to be mean spirited or punitive,” Broerman said.

Whatever Tonkins’ rationale might be, plugging election deniers into clerks’ offices is part of a nationwide effort to destabilize the system, Sean Morales-Doyle, director of the Voting Rights Program for the New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice.

Those bad actors represent a small minority of legitimate poll workers across the country, Morales-Doyle said. But enough of them exist that his organization published guidelines to help election officials ensure that poll workers with ill intentions aren’t able to disrupt elections.

“What’s being done here is an outright attack on our democracy and it’s undermining public faith in our democracy,” Morales-Doyle said. “The more it grows and the longer it goes on, the scarier it becomes.”

“Beyond the pale of absurdity.”

High-profile and far-right personalities like conspiracy theorist Mike Lindell and Trump’s former national security advisor, Michael Flynn, are among those feeding the flames, Morales-Doyle said.

In Colorado, Joe Oltmann is one of those voices, the clerks agree.

Oltmann told The Post that fraud runs rampant throughout the country, particularly with electronic voting machines built by companies like Dominion Voting Systems, Election Systems & Software, Smartmatic and Clear Ballot.

The machines were compromised by “radical leftists,” Oltmann said, and skew results to favor liberal or “establishment” GOP candidates.

Oltmann is quick to mention Eric Coomer, the former director of product strategy and security for Dominion, and share rumors or even lascivious allegations about him.

Conspiracy theories about the voting machines have repeatedly been debunked, but Oltmann said the network of poll watchers and election judges that agree with him will find more evidence. He also said he’s aware of training programs for these people in places like El Paso County, though he doesn’t conduct the training personally.

“We’re very confident we have the people in place to be the final nail in the coffin, to make sure we have enough information in place so we can say ‘here it is,’” Oltmann said. “They’ve stolen the voice of the American people and we’ve had enough.’”

Similarly, Tonkins claims she personally witnessed election fraud in 2020 and accused county officials of refusing to investigate her claim of ballots being cast on behalf of dead people.

That’s not true, Broerman countered. He did receive a list of 759 names from Tonkins, supposed dead people who had also reportedly cast ballots. But it was a “bad list” full of common names like John Smith or Mary Jones, each missing dates of birth.

Of the 759 listed by Tonkins, only one person died and had another person attempt to submit a ballot under their name, Broerman said. County officials caught that one vote even before Tonkins reached out.

“And we had already turned that into the District Attorney for investigation,” Broerman said. “Our system to catch these people works.”

Tonkins went on to question how Trump’s margin of victory decreased in 2020 even though he received more votes than in 2016.

“I’m not a mathematician but I know more means more,” Tonkins said.

Trump’s margin of victory decreased in 2020 because more people voted that year (364,769) than in 2016 (307,115) and because President Joe Biden received a greater share of votes (161,941) than Hillary Clinton (108,010), election data shows.

Broerman said he spent nearly an hour explaining this and more to Tonkins.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, Tonkins and Oltmann suggest that fraud still exists in the country’s electoral system. Plus, isn’t more involvement in the process a good thing, they ask? Isn’t it good to ask questions?

Weld County Clerk Carly Koppes welcomes questions but said at some point skeptics will have to trust her expertise. And some poll watchers aren’t actually seeking answers.

“They’re definitely being trained that they need to find evidence and proof of any and all the conspiracy theories that have been pushed since 2020,” Koppes said.

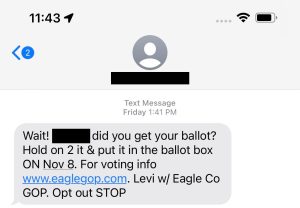

And in some cases the watchers have become confrontational or even tried to infiltrate the election systems, Chaffee County Clerk Lori Mitchell said.

Last year a poll watcher waited until a judge left their post, walked behind a staff counter and wrote down a temporary password for the election system, Mitchell said.

“It was a school board election, if you can believe that,” Mitchell said.

The watcher was quickly caught and forced to discard the stolen password, she said. It wouldn’t have allowed him access to the system anyway because of the county’s two-factor authentication security measures.

“It put us on high alert,” Mitchell said. “You’re just so stunned at the time. It’s just beyond the pale of absurdity.”

Something similar happened in Mesa County in 2020 after Tina Peters, the county clerk there, and a deputy clerk reportedly allowed an unauthorized man to make copies of voting equipment servers. A leading figure in the QAnon conspiracy theory group later posted passwords from the equipment online.

Peters, who later ran – unsuccessfully – for Secretary of State, now faces felony charges.

Mitchell said she also received threatening messages from election deniers claiming she was in cahoots with Dominion’s Eric Coomer, who lives in Chaffee County. She held back tears at the thought.

“It was like ‘We know where you live’ and ‘We’re gonna stake out your town until you give (Coomer) up,’” Mitchell said. “It got very scary for a while there.”

Koppes said things haven’t gone that far in Weld County but she regularly fields loaded or nonsensical questions from people looking for fraud. She laughed, recalling a few.

“One asked me if I could name every wire coming off my computer,” Koppes said. “They definitely have received poor training.”

Koppes said she’s heard that as many as 100 watchers from election denial groups might participate in Weld County’s election in November but expects maybe a few dozen will actually show up.

As an example of the potential damage even one bad judge can wreak, Crane recalled auditing results for the Boulder County Clerk’s Office after the 2020 election. He noticed something off about the work of one Republican election judge.

“In the process of 49 minutes he examined 897 signatures and rejected 889 of them,” Crane said.

While the judge’s intent remains unclear, he risked throwing out the votes of nearly 900 people, Crane said. He was fired and the case was turned over to the district attorney who ultimately did not file any charges.

Fortunately, Crane said a bipartisan team of signature judges caught the error immediately after it happened and overturned 98% of the thrown-out signatures

“The process worked as it should but it’s also why we need to keep pushing forward,” Crane said. “It really is a zero-trust approach to elections.”

Even in smaller places like Fremont County, Clerk Justin Grantham said he’s noticed the trend.

“I have one watcher and he did convey to me that he doesn’t trust the machine,” Grantham said. “He thinks they cheat.”

The clerks all respond to the skepticism with the same message: come see for yourself.

They’re proud of the state’s election system, training processes, built-in redundancies, bipartisan teams, security systems, signature verifications (manual and automatic) and risk-limiting audits.

Garfield County Clerk Jean Alberico said she’s trained multiple people skeptical of the system to be election judges.

“I wouldn’t say they were confrontational but they asked a lot of questions that sort of alluded that things were going on,” Alberico said. “I had them work with my veteran judges and I think it was very eye-opening for them.”

“I don’t know that I completely swayed them but they had their eyes opened,” Alberico continued. “They really understood that we follow some very, very, very tight processes.”

That type of transparency is perhaps the most persuasive argument clerks have, Morales-Doyle said. And they’ll need it because after the November election he anticipates a wave of people refusing to accept the results and then a spat of recount campaigns, like the one that followed Tina Peters’ failed bid for Secretary of State.

The problem is also exacerbated by an increasing number of election deniers running for office across the country, Morales-Doyle said. And just how many people will refuse to accept the results of the November midterms likely depends on the outcomes of those races.

In turn, he’s watching to see how loud the conspiracy theorists blow their horns in November as a possible indication of what lies ahead for the 2024 presidential election.

But if secretaries of state, county clerks, election judges and the general public can hold their ground through the noise in the elections ahead, Morales-Doyle said he’s optimistic the movement will eventually fade away.