They’re not top-of-ticket, but how Coloradans vote on state legislative races will ultimately determine the tack of the state for the near future.

Some voters will have more of a say in that outcome than others. For residents of a half-dozen Senate districts, their votes could ultimately decide if Democrats keep control or if the reins will pass to Republicans.

In the House, most observers bet on Democrats to maintain control. But about a dozen races are competitive and will decide if Democrats keep their well-cushioned majority in the chamber and its committees. Or they could swing red, cut margins and embolden a Republican caucus that is hoping to shake off its history of dysfunction.

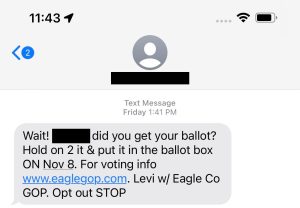

Advertising is raining down on six Senate races. Four will determine if Democrats keep control, or if Republicans flip it

Republicans need to win four seats in the state Senate this November to regain control. Six are considered up for grabs, and millions of dollars are being spent to sway voters.

On paper, all six districts have a Democratic tilt, according to a nonpartisan redistricting staff analysis of recent elections. But the president’s party tends to suffer in midterm elections, and the GOP is hopeful voters are ready for balance after years of Democratic control.

The six districts span the state, from the northwest’s Senate District 8 down to Pueblo’s Senate District 3. Their Democratic tilt in recent years also runs from about a plus 2.4 percentage point advantage in Colorado Springs’ Senate District 11 up to 9.1 percentage points in Thornton’s Senate District 24.

Of all the competitive races, Senate District 15 is theoretically a dead even split — but in a sign of how competitive it may actually be, it’s not drawing nearly the degree of independent spending as the other six. Voters in that district, which covers Loveland and western Larimer and Boulder counties, will decide between Democratic challenger Janice Marchman and incumbent Republican state Sen. Rob Woodward.)

For Dylan Roberts, the money being spent on his Senate District 8 race — and the role it plays in the balance of the senate — translates to campaign trail greetings regularly being met with, “Oh, I’ve seen you on TV!”

The district has been subject to nearly $4 million in independent spending, both specifically on that race and group efforts, by third parties.

“It’s intense for voters,” Roberts said.

The deluge has led both him and Republican Matt Solomon to say they need to distance their campaigns from what outside groups say, especially when they’re sending more negative messages.

Each also said majority control of the senate, while part of the political equation, isn’t front of mind for voters in the district. Instead, the voters want officials to represent interests that include ski resorts and ranching. For Solomon’s part, he highlights his background in the public and private sectors as proof of his ability to navigate what’s best for the district, and not just the party — and that a split legislature can force overall better outcomes for people there through compromise.

“Having a balanced legislature, having a backstop in the Senate, it really does bring about better policy,” Solomon said. He added, “If you have super far-wing legislation coming down the pipeline, one way or the other, the other chamber is going to stop that.”

Roberts said most voters he talks to care more about what he can deliver, and has delivered, than which party controls the Senate, even as they feel the advertising downpour that comes with deciding a potential balance-of-power seat.

Roberts, like most of the Democrats in the six most targeted races, isn’t an incumbent but does have a years-long record in the legislative majority to run on, or be attacked with.

He points to his bills to lower insurance premiums, deliver affordable housing grants, and cap insulin prices as highlights.

“Whether I’m in the minority or the majority, my bills and the topics that I would focus on wouldn’t change that much,” Roberts said, adding that almost all of his bills have had bipartisan support. “… As far as other bills that other legislators bring, that, of course, could hinge on which party is in the majority of either chamber.”

In Senate District 24, which covers Thornton, the voters are keenly aware of the weight of their vote this November, Democrat Kyle Mullica and Republican Courtney Potter agreed. In addition to being a potentially pivotal seat for the state senate, those voters are also coveted for the 8th Congressional District — one of the tightest and most closely watched races for the U.S. House of Representatives and a potentially pivotal one for which party controls that chamber, too.

That state senate race is part of nearly $4 million worth of independent expenditures so far this season, even though it has the largest pro-Democrat gap in recent races.

“The amount of money coming in really does emphasize the importance of this race, and I think really underlines the importance of regaining balance here in Colorado,” Potter said.

A Republican majority in the senate would serve as a “check and balance” on some of the more extreme proposals that emerge, either by modifying them or outright halting them, Potter said. She highlighted Democrat-led pushes to defelonize drug possession, including fentanyl — since modified — and criminal justice reform that she blames for rises in things like car theft.

Many of those reforms had some bipartisan support but largely passed along party lines. Democratic arguments generally say they’re aiming for harm reduction and trying to combat inequalities and over-incarceration.

On the other side of the coin, Mullica highlights the importance of Democratic majorities for protecting the rights of trans people, gay marriage and abortion. He cites the Reproductive Health Equity Act, which codifies abortion access into state law, as a case where Coloradans are “one majority away from losing that right.”

“There’s a range of issues where we can lose some of the growth we’ve had over the past 10-15 years,” Mullica said.

His community agrees things like affordability and crime are problems that need solving, even if there are disagreements about the solution. He points to the top of the Republican ticket and gubernatorial candidate Heidi Ganahl’s recent debunked warnings of “furries,” or kids identifying as animals in schools, as evidence that Democrats are more serious about tackling them.

“This community is focused on real issues,” he said. “(The Republicans) are focused on the furry thing.”

In an interview, Potter didn’t say one way or another if she shares Ganahl’s furry-specific concerns, but instead that she has broad concerns with children’s mental and social well-being coming out of the darkest months of COVID.

In House, the difference between slim and solid majorities

The November election comes at a moment of transition for both parties in the House. The Democrats wield a near two-to-one majority and firm control of committees. Their broader control seems assured heading into Election Day, and officially, Democratic leaders say they’re optimistic they can at least maintain their 41-seat stronghold.

Still, they acknowledge that redistricting has made the chamber more competitive, and midterm elections for the party in the White House are often unforgiving. If they end November with relatively few losses, several said, the election could still be seen as a success.

Republicans, meanwhile, are hopeful that their years of infighting and self-sabotage are at an end, with internal dissidents like Reps. Dave Williams and Patrick Neville out. While Democrats said some Republican candidates could become new bomb-throwers — Kennedy used the term “spicy” to describe some of them — Republicans are preaching a new, unified caucus.

“I think this is going to be the most cohesive, cooperative and just dynamic group of people that the House has seen for a really long time,” Minority Leader Hugh McKean declared in late September. It’s a sentiment echoed by Republican Rep. Colin Larson, who celebrated the departure of “charlatans” like Williams and Neville.

Democrats (and some Republicans) aren’t exactly buying that — Rep. David Ortiz, himself in a tight race, quipped “we’ll see” when asked about the Republicans’ sunny outlook. Williams called it “naïve and arrogant” for McKean to think the caucus would heal just because he and others were out of it.

Democrats will have to contend with shifting membership, too. Both Speaker Alec Garnett and Majority Leader Daneya Esgar are term-limited, and other moderate veterans are pursuing Senate seats. At the same time, new voices are emerging: Elisabeth Epps beat Katie March in an expensive — and caustic — June primary, and she and fellow activist Javier Mabrey are expected to strengthen the progressive wing of the caucus.

“I think the call to public service is what you’re going to see uniting every single member of new Democratic caucus,” Rep. Mike Weissman, an Aurora Democrat, said. “And I think from that common ground and common perspective, I think that we will forge continued unity and service of the needs of the people of our state.”

But before they can begin debating how everyone will get along, the Democrats will have to defend their majority, and Republicans have targeted several races across the state as likely pickups. All of them are considered Democrat-leaning, though some are only just.

In northwest Colorado, Democrat Meghan Lukens and Republican Savannah Wolfson are vying for House District 26. According to the redistricting committee, the area is narrowly Democrat-leaning, and Lukens, a history teacher, has more than twice the amount of money as Wolfson entering October.

Still, Wolfson said she was hopeful, and she downplayed the impact of national moves on her race. Voters are focused on Colorado issues, she said.

“I actually get the sense on the ground that most people aren’t paying attention until the last minute,” she said. “When I door-knock, people are mostly thinking about housing. … What every single county and town share in common is they really want housing, and there’s a shortage.”

In El Paso County’s House District 18, Democrat Marc Snyder is seeking a third term against Shana Black in a race that the redistricting committee effectively dubbed a toss-up. Snyder’s outraised Black, and he told The Denver Post he thinks his credentials as a bipartisan, centrist Democrat will help him in a conservative county.

Snyder acknowledged that his race is, on paper, among the most competitive in the state. He felt bolstered by the “sea change” he’s felt over the past few months, but he said he’d need to convince people unhappy with national leaders to vote for him anyway.

In Arapahoe and Douglas counties, Democrat Eliza Hamrick and Republican Dave Woolever are jostling for the House District 61 seat. The redistricting committee has it rated nearly as tight as Snyder’s race, with a 0.5% edge for Democrats. Like other races, the contest will come down to how unaffiliated voters swing: The district has more than 28,000 unaffiliated residents, at least 10,000 more than the number of registered Democrats or Republicans.

In the south metro, Ortiz is working to fend off a challenge from Republican Jaylen Mosqueira, a former campaign and legislative aide in House District 38, which leans Democrat by 2.9%.

Ortiz said he’d been struck by the number of people he’s talked to who’ve never spoken to a candidate or representative before. It shows neither party did the work in years past, he said.

Democrats need to talk up their wins, he continued, while acknowledging that risings costs are hurting people. While Republicans have sought to tie Democratic spending and their opponents’ broader handling of the economy as the sole cause of inflation, Ortiz and other Democrats said it was more complicated than that.

“Inflation’s not something Democrats did,” he said.

Other tight races include House District 13, where Rep. Julie McCluskie is fighting David Buckley; House District 28, where Democrat Sheila Lieder — a last-second replacement for primary-winner Leanne Emm — and Republican Dan Montoya are vying for a vacant seat; and House District 59 in southwest Colorado, a battle between incumbent Democrat Barbara McLachlan and Republican Shelli Shaw.

Those races could determine not just the size of the Democratic majority in the House but who leads the chamber. McCluskie is one of three candidates for speaker, several Democrats said, alongside Reps. Chris Kennedy and Adrienne Benavidez. Kennedy acknowledged he was running to become speaker and expressed optimism for the party going forward.

“We have a good chance,” he said, “of upsetting the normal midterm trend.”